The Michigan Public Trust Doctrine

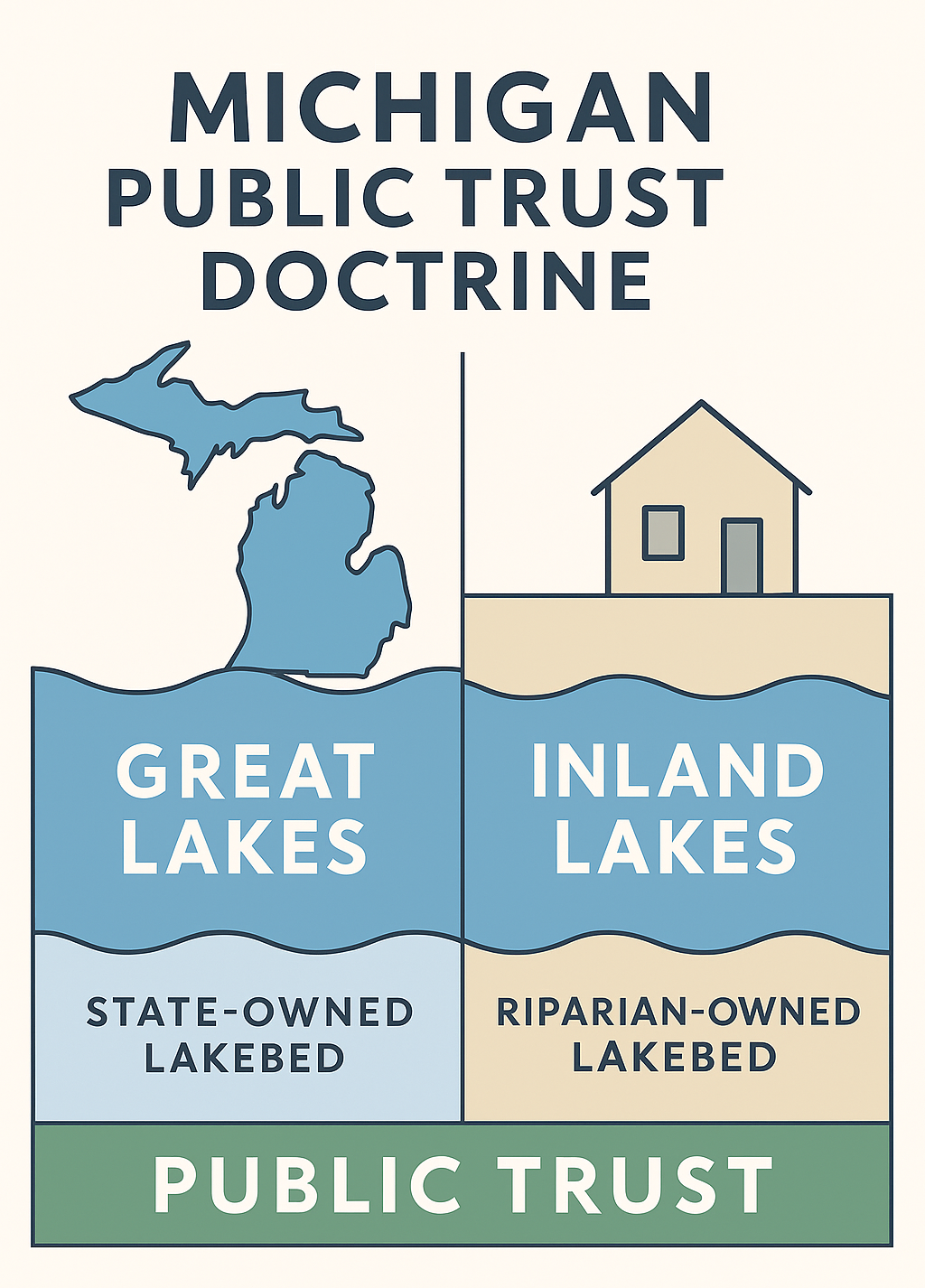

The concept of the public trust is one of the oldest and most important doctrines in Michigan water law. Rooted in English common law and reaffirmed in a long line of Michigan cases, it holds that certain waters are preserved for the use and enjoyment of the public, and that the state serves as trustee to protect those interests. While the doctrine applies broadly, there are key differences in how it functions with respect to the Great Lakes compared to Michigan’s thousands of inland lakes.

Origins and Core Principles

The public trust doctrine in Michigan is derived from common law notions that navigable waters belong collectively to the people. This doctrine was inherited from English law, where the Crown held navigable waters in trust for fishing, navigation, and commerce. When Michigan became a state in 1837, ownership of the beds of the Great Lakes within Michigan’s boundaries passed to the state, subject to the public trust.

The Michigan Supreme Court has consistently recognized that the state holds these waters and submerged lands in trust for the people, and that the legislature cannot abdicate this duty. Courts have emphasized the state’s role as trustee of the Great Lakes, and have followed that principle ever since.

The doctrine protects traditional uses such as navigation, fishing, and commerce, but over time it has been expanded to encompass modern uses such as swimming, boating, and even environmental protection. Courts have recognized that the doctrine is flexible, evolving to meet new understandings of public needs.

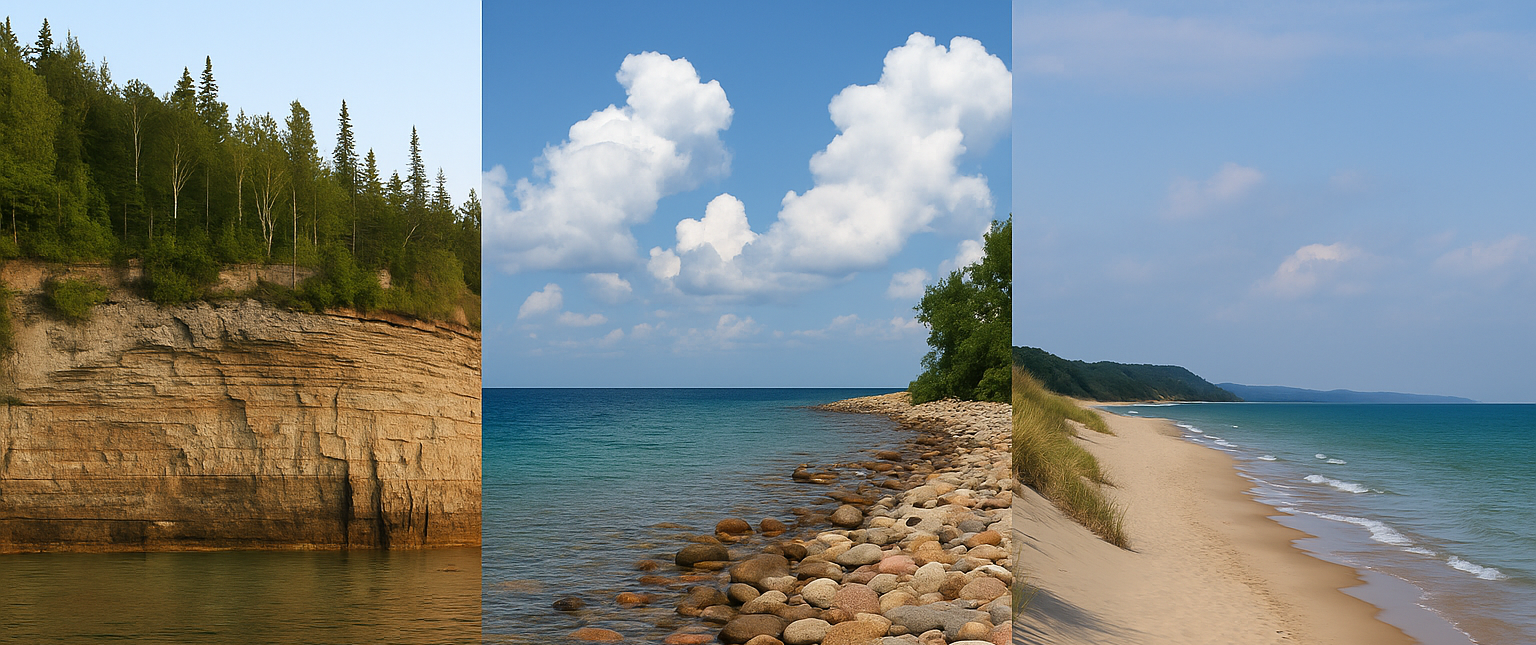

The Great Lakes: Unique Public Trust Status

The Great Lakes—Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie—have the strongest and clearest public trust protections. Under Michigan law, the state owns the beds of the Great Lakes up to the ordinary high-water mark, and this ownership is held in trust for the public. This was made explicit in the landmark case Glass v. Goeckel in 2005.

In Glass, the Michigan Supreme Court held that members of the public have the right to walk along the shore of the Great Lakes below the ordinary high-water mark, even across privately owned upland property. This ruling reinforced that the state’s obligation under the public trust doctrine extends beyond navigation and fishing—it also includes recreational walking and access.

The Great Lakes are considered part of a sovereign trust resource: their size, international significance, and role in commerce make them fundamentally different from smaller water bodies. For this reason, the public’s rights are expansive, and riparian owners on the Great Lakes hold title only to the ordinary high-water mark. Above that line, their ownership is private; below it, the land is subject to "the public trust."

Inland Lakes: Limited Public Trust Application

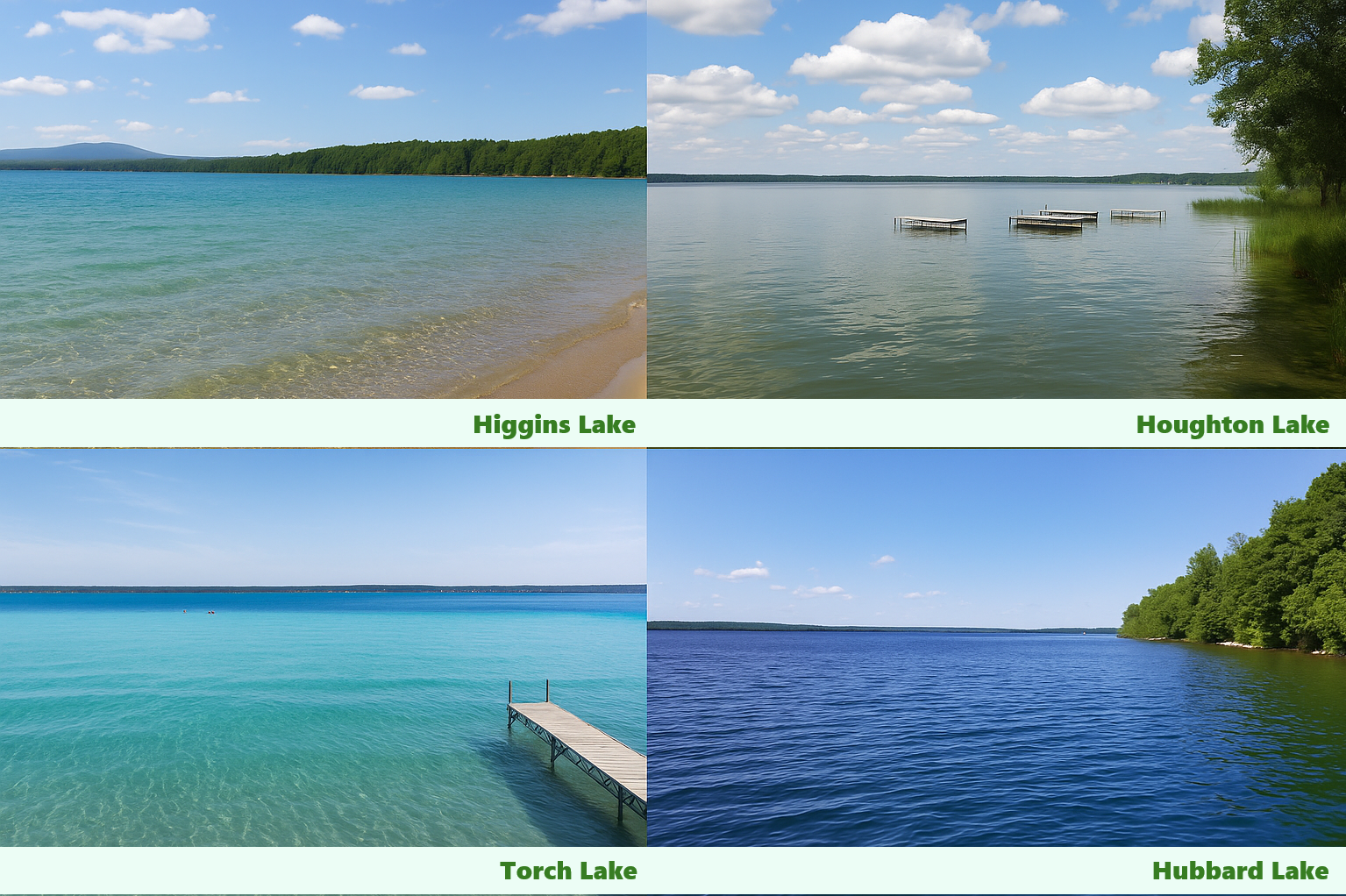

By contrast, Michigan’s inland lakes are not automatically subject to the same sweeping public trust principles. Instead, the doctrine applies primarily to waters that are navigable-in-fact—that is, lakes and streams that can serve as highways for commerce in their natural condition. This test dates back to cases like Collins v. Gerhardt (1925), where the Michigan Supreme Court emphasized that waters capable of navigation are held in trust for the public.

Most inland lakes in Michigan are small and privately owned by the surrounding riparian landowners. For these lakes, the beds of the lakes are typically divided among riparian owners, and the public has no general right of access unless there is a public dedication, road end, or other specific legal right of entry. In other words, the public trust doctrine does not create a general public right of access to every inland lake.

However, when an inland lake is navigable, or has been declared a “public lake,” the doctrine does apply, ensuring that the waters can be used for boating, fishing, and related activities. The distinction lies in ownership: whereas the state owns the bottomlands of the Great Lakes, private riparian owners usually own the bottomlands of inland lakes. The trust in this setting applies to the use of the waters, not the ownership of the land beneath them.

Practical Implications of the Differences

| Great Lakes | Inland Lakes | |

|---|---|---|

| Access and Use | The public has the right to access, walk along, and use the shorelines below the high-water mark, regardless of adjacent private ownership. | Public rights are limited to navigable waters and specific access points (like public boat launches or platted road ends). There is no general right to cross private property to reach an inland lake. |

| Ownership of the Lakebed | The state owns the lakebed up to the high-water mark, in trust for the people. | The lakebed is owned by the riparian property owners, subject only to the public’s right to use the water if it is navigable. |

| Ownership of the Lakebed | Environmental concerns such as wetland protection, shoreline erosion, and pollution are framed as part of the state’s public trust duty. | Environmental protection relies more heavily on regulatory statutes (e.g., NREPA) rather than broad constitutional trust principles. |

The public trust doctrine in Michigan represents a powerful guarantee that water resources will be protected for public benefit. But it is not uniform across all waters. The Great Lakes receive the broadest protection, with the state owning and managing bottomlands up to the high-water mark. Here, the doctrine assures expansive public rights of access and recreation.

By contrast, inland lakes operate under a narrower version of the doctrine. Unless navigable or otherwise designated public, they remain largely the domain of riparian property owners, with the public’s rights confined to navigable use and designated access points.

This subtle but important distinction reflects Michigan’s dual heritage: steward of the world’s largest freshwater system while also home to thousands of smaller, often private, inland lakes. Both settings demonstrate the enduring significance of the public trust, but in ways carefully calibrated to the character of the waters involved.

→ Related: Docks and Piers