Determining Property Lines Underwater

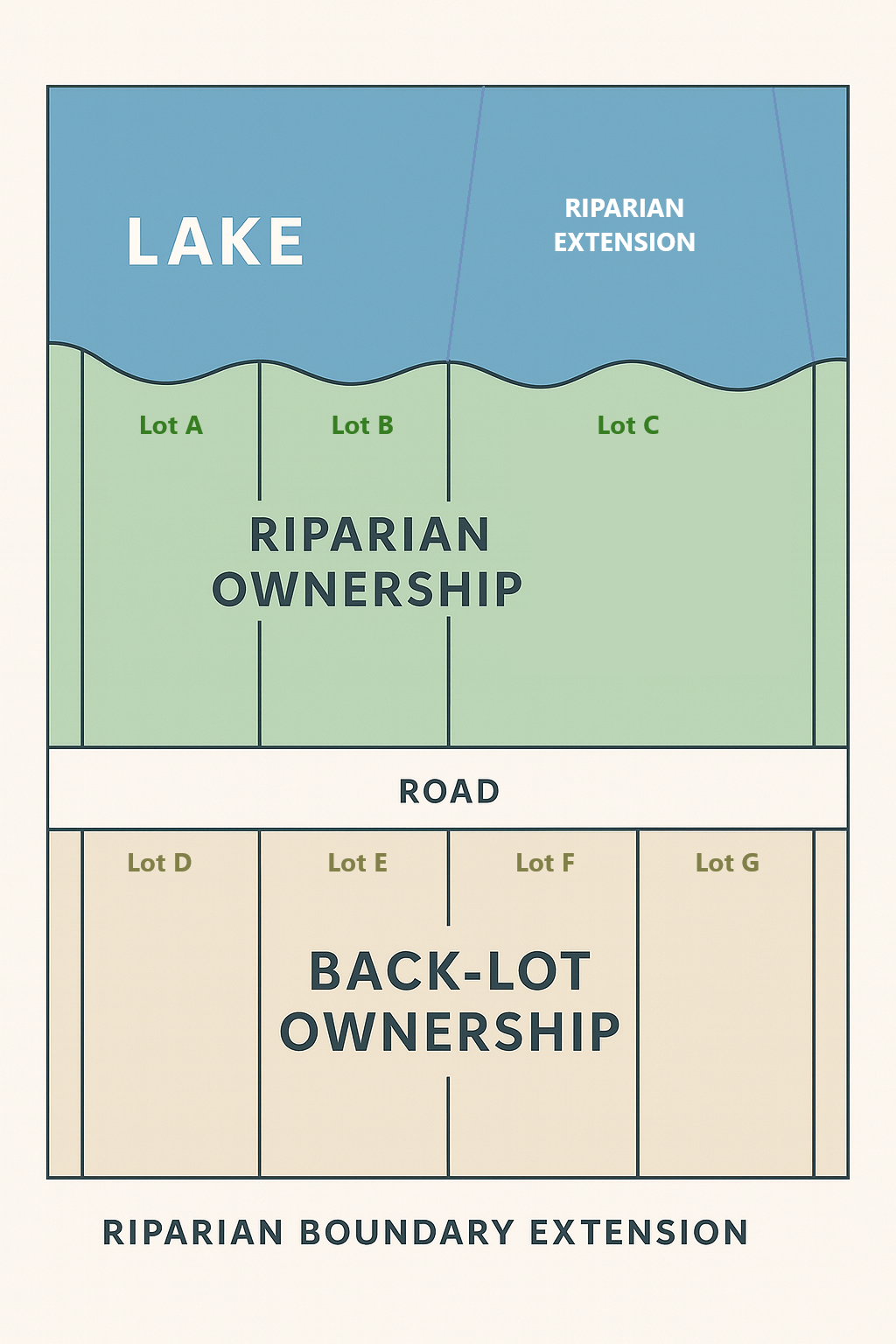

One of the most complex aspects of riparian law involves the unseen boundaries beneath the water’s surface. In Michigan, a riparian owner’s property extends beyond the shoreline into the lake or river bottomlands. But where exactly does one owner’s bottomland end and the neighbor’s begin?

Courts use several methods to apportion riparian boundaries, particularly on irregularly shaped lakes. In many cases, lines are drawn to create wedge-shaped parcels pointing toward the center of the lake.

But this does not work in all circumstances. The goal is always the same: to distribute access to navigable waters fairly among neighboring riparian owners.

Boundary disputes often arise when docks or boat hoists appear to cross into another owner’s bottomlands. Resolving these disputes may require surveys, aerial photos, and, in many cases, legal action. Because bottomland ownership is tied directly to riparian rights, boundary disputes are taken very seriously in Michigan courts.

The Doctrine of Riparian Extension in Michigan

One of the most perplexing aspects of Michigan riparian law is the question of where a landowner’s rights end once his or her upland parcel meets the water. While ownership of the upland is readily determined by the recorded deed and survey boundaries, matters become more complicated when those boundaries intersect with a lake, pond, or stream. Because water itself cannot be subdivided or partitioned like land, the law has developed doctrines to allocate “underwater boundaries.” These underwater boundaries govern critical rights: the right to build docks, to moor boats, to install structures such as hoists or seawalls, and even to exclude others from the immediate offshore area.

The Michigan Court of Appeals case Heeringa v. Petroelje, 279 Mich App 444; 760 NW2d 538 (2008), remains the most direct judicial attempt to articulate the law of riparian extension into a lake. But while Heeringa gives useful guidance, it also contains a significant shortcoming: the case arose on a perfectly round inland lake. As anyone familiar with Michigan’s landscape knows, most lakes are irregular—crescent-shaped, oblong, with coves, peninsulas, and bays. Applying a round-lake formula to irregular lakes creates serious uncertainty.

The Holding in Heeringa v. Petroelje

In Heeringa, the dispute involved whether one riparian owner’s dock and boat mooring interfered with the rights of the neighboring riparian. The Court of Appeals recognized the longstanding doctrine that each riparian is entitled to a reasonable use of the surface waters in front of his or her lot. To effectuate that principle, the court described a method for projecting lot lines into the water in order to delineate a fair offshore boundary.

The court adopted the “pie-shaped” rule: when riparian parcels meet the shoreline of a round lake, the underwater boundaries should be drawn as radial lines projected toward the center of the lake. Thus, the underwater parcel looks like a slice of pie, with the crust being the shoreline frontage and the point being the center of the lake. The idea is that this allocation maximizes fairness, since each owner receives an offshore wedge proportionate to their frontage.

The Heeringa court also emphasized that the governing standard is one of “reasonableness.” In other words, riparians may use the waters in front of their property in a way that is reasonable relative to other riparians. Courts should consider the shape of the shoreline, the number of owners, and the type of uses being made. The underwater boundary is therefore not a rigid surveyor’s line, but a practical construct used to allocate competing rights.

The Shortcoming of the Round-Lake Model

The difficulty is that few Michigan lakes are truly round. In reality, many lakes are highly irregular. For example, Higgins Lake is oblong and stretches miles in length. Houghton Lake has extensive bays and coves. Other lakes feature peninsulas that jut into the water, or even islands. Applying the Heeringa “pie slice” model to such lakes is often unworkable.

Consider a long, narrow lake. If the radial method were used, underwater lines drawn toward the “center” would converge at a distant point, giving some owners almost no usable frontage offshore while giving others massive tracts. Similarly, on a concave shoreline such as a bay, radial projection would result in overlapping underwater parcels, creating disputes rather than resolving them.

The Heeringa decision did not squarely address these situations, because the case arose in the uniquely neat context of a circular lake. This has left Michigan riparians and lower courts without clear guidance when facing the far more common problem of irregular shorelines.

Alternative Doctrines and Approaches

Michigan courts and commentators have suggested several possible approaches to handle irregular lakes:

Perpendicular Projection – Some recommend that underwater boundaries be projected as perpendicular lines extending outward from the shoreline at the point where the upland boundary meets the water. This can work well for relatively straight shorelines but becomes difficult at sharp curves or in bays.

Equitable Division Based on Shoreline Length – Another approach divides the offshore area proportionately to the length of shoreline each owner possesses, sometimes creating irregular polygons offshore. This method seeks to preserve proportionality but may yield odd geometries.

Reasonableness Test Alone – Rather than fix geometric boundaries, some courts simply apply a case-by-case “reasonable use” test. This recognizes that riparian rights are inherently flexible, but it sacrifices predictability and makes disputes more likely to reach litigation.

Hybrid Approaches – In practice, Michigan courts often blend these doctrines. For example, in a straight shoreline, perpendicular projection may be applied. In a round lake, radial projection (as in Heeringa) is preferred. In more complex settings, courts lean heavily on reasonableness (which means uncertainty).

Policy Considerations

Underlying the doctrine of riparian extension is a balance between two competing policies. On one hand, the law wants to respect private property rights, giving each riparian a definable offshore area. On the other, the law recognizes that water is shared and must be used in a way that avoids conflict and preserves public trust values. Michigan’s public trust doctrine overlays all riparian rights, ensuring that navigation, fishing, and boating remain open to the public.

When underwater boundaries are unclear, conflicts escalate: one owner’s dock blocks another’s access; one moors boats in a manner that prevents neighbors from reasonably using their frontage. The absence of clear lines drives litigation, with courts forced to craft ad hoc solutions. The Heeringa case gave some structure, but its utility is limited outside the round-lake context.

Practical Implications for Riparian Owners

For riparian property owners, the lesson is that underwater rights cannot be determined merely by looking at the deed. Instead, owners must consider the shoreline’s shape, the location of neighbors, and the reasonable use standard. Building a dock or mooring a boat without accounting for these doctrines risks encroachment claims.

Surveyors and attorneys can assist by preparing “riparian extension surveys” that project underwater boundaries using the most defensible method for the particular lake. Yet even these surveys remain subject to judicial review, because the controlling legal principle is reasonableness, not strict geometry.

Until Michigan’s appellate courts squarely address these more difficult cases, riparian owners will face continued uncertainty—and likely litigation—over the true extent of their underwater boundaries.